Comptes Rendus Palevol

15 (1-2) - Pages 40-48

Comptes Rendus Palevol

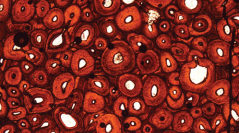

15 (1-2) - Pages 40-48We propose the hypothesis that in the long bones of large, rapidly growing animals, secondary osteons may form to a greater degree in smaller bones than in larger ones for reasons that may have more to do with the interplay between element-specific growth rates and whole-body metabolic rates than with mechanical or environmental factors. We predict that in many large animals with rapid growth trajectories and some disparity in size in the long bones and other skeletal elements, the largest bones will show less secondary remodeling than smaller ones. The reason is that, whereas the largest bones are increasing their dimensions too rapidly to accommodate much secondary reworking (until they approach full size), the smaller bones that are not increasing in size as rapidly must still process the flow of metabolites through their elements, and this is manifested in secondary remodeling. This hypothesis does not contradict or undermine other explanations, but rather adds an additional one that focuses more on growth and metabolic rates with respect to bones of different size in the same skeleton. Because the timing of onset of remodeling and the pace of its progression both vary by element, caution must be taken when using secondary remodeling to infer the overall ontogenetic stage of the animal.

Paleohistology, Vertebrate paleontology, Growth rate, Physiology, Bone histology