Anthropozoologica

58 (5) - Pages 59-72

Anthropozoologica

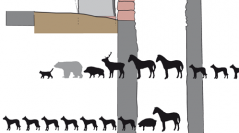

58 (5) - Pages 59-72In Roman times, the brown bear (Ursus arctos Linnaeus, 1758) was one of the most important hunted wild animal species. Bears were killed for e.g. their furs, their teeth and their meat. One of the reasons for catching bears alive was for their use in the context of public entertainment, i.e., animal hunts in amphitheatres. Bear bones from the Roman settlement of Augusta Raurica, NW Switzerland, attest the tradition of hunting (or trading?) bears in this part of the Roman Empire. Archaeozoological investigations of several complete bear skeletons from this site indicated that at least one bear was kept in captivity for some period. The remains of four bears, deposited in two wells, were selected for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis to explore whether life (stages) in captivity had an impact on the diets and in consequence to the stable isotope ratios in bear bone collagen. A comparison with (herbivorous) horses and (omni-)carnivorous dogs from the same Roman city and with bears from other prehistoric and modern contexts indicates that the diet of the adult brown bear specimen from Augusta Raurica was plant-based and does not provide evidence of human-influenced feeding in (prolonged) captivity. Nitrogen enrichment in the young bears is most likely explained by suckling. Human-influenced additional feeding in captivity cannot be completely ruled out but the enrichment results from stable isotope data from wild brown bear data from the literature and from dogs and equids from the same site argue suggest that this was not taking place.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes, Roman period, NW Switzerland, diet, captivity.